2199. Deep-space exploration is a reality and teleportation is routine.

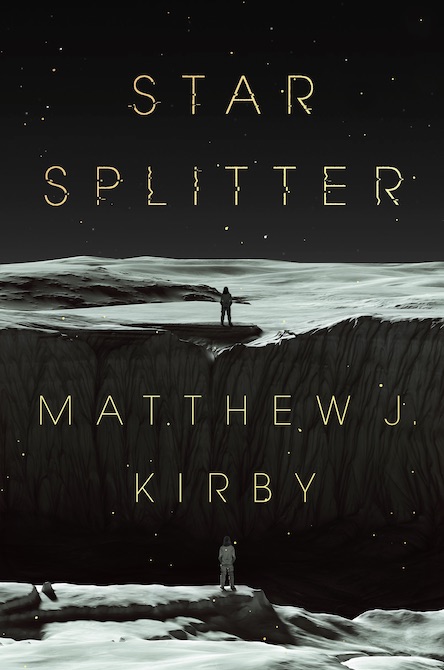

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from young adult science fiction novel Star Splitter by Matthew J. Kirby, out from Dutton Books for Young Readers on April 25.

2199. Deep-space exploration is a reality and teleportation is routine. But this time something seems to have gone very, very wrong. Seventeen-year-old Jessica Mathers wakes up in a lander that’s crashed onto the surface of Carver 1061c, a desolate, post-extinction planet fourteen light-years from Earth. The planet she was supposed to be viewing from a ship orbiting far above.

The corridors of the empty lander are covered in bloody hand prints; the machines are silent and dark. And outside, in the alien dirt, there are fresh graves carefully marked with names she doesn’t recognize. Now Jessica must unravel the mystery of the destruction all around her—and the questionable intentions of a familiar stranger.

The room only had a single hatch. I moved toward it, and through its window I glimpsed a narrow passageway that looked a lot like the corridors back on the Liverpool. Except this one curved away into darkness, illuminated only by its dim red emergency lights. I looked at the control panel to my right, and after a moment of hesitation, I used it to open the hatch.

Buy the Book

Star Splitter

The air in the passage felt looser and smelled less stale, and now I could hear deep, metallic groans and distant pops from elsewhere in the ship.

I called out. “Hello?”

My voice echoed down the passageway. No one answered.

I held my breath and slipped through the doorway, then eased along the corridor one careful step at a time, listening and squinting in the rusty light. Several panels there had also been torn away from the walls, baring the ship’s innards. I saw deep gouges in the metal and plastic. I passed three open hatches on my right, but the rooms were pitch-dark and empty, or at least I hoped they were as I hurried by them.

The corridor eventually ended at another closed hatch. When I reached for the control panel, I noticed a few dabs of dark stain on the buttons, and a partial, ruddy handprint on the wall. I stared for a moment, feeling a prickle at the nape of my neck, before finally opening the door.

Natural light poured over me into the passageway. Not ship light, sunlight. I shielded my eyes for a moment, and after my vision adjusted, I found I had reached a juncture where my corridor met with three others. The one to my left seemed like an external air lock. Then I noticed the walls, and my throat tightened.

Handprints painted the panels of the juncture in reddish-brown smears that definitely looked like dried blood. Leathery, crackled puddles of it covered the floor, as if a body or bodies had broken right there, at that spot. I smelled decay in the air and swallowed, finding it hard to breathe as I tried not to imagine the violence that must have taken place there, hoping my parents were okay, wanting suddenly to get out of there.

One of the few things I did know about Carver 1061c—if I was on Carver 1061c—was that it had a breathable atmosphere, and I stumbled toward the air lock. I had no idea what waited for me outside, but I knew I didn’t want to stay on the ship, so I opened the internal hatch, entered the air lock, and then opened the external hatch.

A warm breeze rushed in, smelling faintly of old pennies and moss, but clean, and it brushed a few grains of sand against my cheek. I inhaled, able to breathe clearly again, and stepped over the threshold onto dark, alien dirt flecked with gold and green.

The broken and uneven landscape spread out in all directions. Brown hills rose and fell in sharp folds, covered in patches of the purple vegetation that I’d seen through the portholes. They reminded me of ferns. I took a few steps away from the hatch, wanting to get a better look at the ship from the outside, hoping for a clue to figure out where I was and how I got there, but then I saw the volcano, and I had the answer to the first question.

Mount Ida. The killer of Carver 1061c.

I couldn’t tell how far away it was. With something that big, normal scale doesn’t apply. Its base spread over most of the horizon. Its volcanic slopes rose through several layers of clouds, reaching an altitude so high that I had to crane my neck to see its conical peak. The mountain ruled over the landscape so completely that it seemed to have its own demanding gravity, and I found it hard to pull my eyes away from it, back to the ship.

When I did, I discovered I was right before. It wasn’t the DS Theseus. At least, not all of it.

The large letters on the battered skin of the vessel told me I had emerged from the port side of one of the Theseus’s landers, but huge chunks of it seemed to have been ripped off. Other parts had been caved in, deforming its teardrop shape with massive dents. The areas of its belly that I could see bore the scorch marks of atmosphere re-entry, and some of the heat shielding had been torn away. Whatever had brought it down here from orbit, the trip hadn’t been easy. It didn’t even look like the landing gear had deployed.

I looked up at the sky and wondered if the lander’s parent ship was still in orbit, and if my parents were still on it. I stared into that blue void so long my eyes watered, and I got dizzy running through the reasons an evacuation of the Theseus might have been necessary. An emergency of some kind, for sure, but something very, very bad. There weren’t that many possibilities, according to the safety presentation on high-orbit and deep-space ships that ISTA had made me watch. Externally, an asteroid strike or a solar flare could do it. Internally, one of the main systems would have to malfunction in a catastrophic way, like a reactor failure.

I looked down at my hands. If something had gone wrong with the reactor, the body that had just been made for me might have been bathed in radiation while it was still being printed. I had no idea what that would mean, but my guesses ranged from cancer to mutant monster, even though I looked and felt fine.

A cloud passed in front of the sun. I figured that’s what I might as well call the star in the sky. The deep shade gave me chills as it glided over me, the lander, the ground, and then the sun came back. I decided to circle the lander, just to see if I could find any more clues about the catastrophe that had brought it down, and I moved toward the rear of the ship.

As I came around the back, I saw the deep furrow the lander had carved in the skin of Carver 1061c as it crashed. That trench must have been a mile long, and I had to climb down into it and back out again, pulling against the planet’s extra gravity to reach the opposite side of the ship. The damage there looked a lot like what I had seen on the first side, but I found the greatest destruction at the front, where the cockpit had been completely crushed. I knew the pilot’s body couldn’t have survived the impact.

As I returned to the side of the lander I had come out of, something caught my eye a short distance away. It looked like a mound of soil, but its shape was too regular to be natural. I moved toward it, already somewhat out of breath from the walking I’d been doing. The planet’s gravity had been slowly getting to me, growing more insistent. My feet felt heavier. My whole body felt heavier, and I moved more slowly because of it.

When I approached the mound, I saw three more just like it nearby. Each was about a meter wide, and about two meters long, the dirt dry and packed hard. Then I noticed the signs, and my stomach turned. Someone had attached name badges, like the patches on uniforms, to pieces of scrap metal from the ship and placed one at the head of each mound. Each grave.

I made myself read them.

Rebecca Sharpe

Evan Martin

Elizabeth Kovalenko

Amira Kateb

Alberto Gutiérrez

The last plaque was different from the others. No badge, no mound, just a name scratched into a piece of metal, marking a flat patch of dirt next to the others. I sighed, relieved that none of the names belonged to my parents, and that none sounded familiar. Then I felt a bit guilty, because even though I didn’t know those people, someone had cared enough about their broken bodies to bury them.

“What happened to you?” I whispered.

I shivered and turned away. Cemeteries had always freaked me out because graves were for your last body. They were terminal. I hurried back toward the broken nose of the lander, but as I moved around it and down the side of the ship, something rustled the purple ferns on my right.

I jumped and spun to face it but saw nothing except the plants swaying a few meters away. Their stalks only came as high as my knees, so whatever was out there, it was low to the ground.

I kept my back against the lander, watching the ferns as I slowly inched toward the hatch. Not that I wanted to go back inside the ship, but that seemed better than staying outside it with some kind of alien. I’d never seen an extraterrestrial life-form before, but I had just seen five graves, so it was easy to imagine something deadly lurking out there. Something with fangs. Or claws. Or venom. Or all three. Or something completely alien and far worse.

Or it could be totally safe, like a puppy. If I had read the shit my parents had sent me, I might have known what it was. But I hadn’t read the shit my parents had sent me, so I crept away from it, refusing to blink or breathe, watching.

I’d moved a few meters when the thing burst through the ferns toward me. I almost bolted, but then it stopped, still hidden in the vegetation, clearly able to see me or sense me in some way.

I tried to reassure myself that its behavior might not be hostile. It might instead be evidence of curiosity, or even its fear of me, and its need to observe me in case I was the kind of threat I feared it to be. But since I had no way of knowing its intent, I continued to hurry down the side of the ship toward the hatch, expecting it to follow me.

But the ferns didn’t move, and I wondered if the alien was still watching me, or if it had simply decided that I was neither interesting nor a threat. Then something stirred the plants much closer, directly in front of me, scratching in the dirt and snapping stems and fronds.

There were two of them.

“Stay back!” I shouted, without even knowing if the things had ears. “Both of you!”

“There’s only one of them.”

I flinched at a very familiar voice. An impossible voice.

She stood in the doorway to the air lock, one foot in, one foot out. She wore the same boots I wore, and she wore the same type and size of jumpsuit, though her clothes were dirtier than mine. She wore my face, though it was dirtier, too. She wore my hands, and my body.

She was me.

Not metaphorically. She didn’t look like me. She was me.

A horrified shock immobilized every muscle, my mouth stuck in the open position. In that moment I lost every thought that had been in my head. I lost Carver 1061c, and I lost the alien somethings. I lost myself, even as I was looking at myself.

“They live underground,” she said with my voice, nodding toward the ferns. “Come inside. I’ll explain everything else.”

Excerpted from Star Splitter, copyright © 2023 by Matthew J. Kirby.